Well You Might Ask

Well You Might Ask

By David Clemmer

With the advent of the modern era, progressively-minded artists were compelled to question the validity of inherited assumptions regarding the practice and function of the visual arts. Many artists of the twentieth century found established figurative modes inadequate to their purposes and created idiosyncratic new visual vocabularies with which to articulate their conceptions of the human condition. Artists of the postmodern generation(s) have, in turn, challenged the tenets of the modernist agenda. It is now accepted practice to sample and revise at will from the vast history of painting and sculpture - abstract and representational alike - and to mix and match freely from both “high“ and “low“ cultural sources. The case of Michael Scott, however, presents us with a curious conundrum. While not possessed of a “typical“ postmodern sensibility (should any such condition actually exist), Scott is an artist who simultaneously utilizes and satirizes postmodern strategies in order to address complex ideas regarding science, aesthetics, and spirituality. With liberal borrowings from the historical idioms of portraiture, landscape, and still life, Scott creates a unique blend of whimsy and philosophical discourse. All good and fine, you might say, but what’s the deal with the chickens? Well you might ask...

Artists of earlier times, typically addressing religious or historical themes, were bound to express human ideas and ideals in a literal manner through the depiction of human subjects. With the rise of Symbolism and allegorical painting in the latter half of the nineteenth century, a greater range of conceptual possibilities was made available to the artist, including the assigning of human (as opposed to divine or supernatural) qualities to non-human actors. Animal characters with human attributes have been a feature of children’s fables for centuries, and in more recent years this device has become a staple of popular genres such as cartooning (of both the political and strictly humorous varieties) and animated films and television programs. In the world of fine arts, the strategy of anthropomorphism has been employed by a diverse range of acclaimed artists, including Pablo Picasso, Marc Chagall, Max Ernst, Roy Lichtenstein, Jeff Koons, William Wegman, and Donald Roller Wilson (for the latter two artists, the use of animal characters constitutes a primary motif). As for Michael Scott, his birds can boast a proud conceptual pedigree that extends from Mother Goose to Foghorn Leghorn.

While there is an aspect of the comic inherent in most anthropomorphism, many artists have taken advantage of the capacity for animal characters to act out with greater freedom and less self-consciousness than might be available to their human counterparts. Well aware of this, and far from being satisfied with simple slapstick antics for his avian menagerie, Michael Scott has conceived of an entire world (one which exists in conjunction with, yet somehow separate from, our own) populated by a colorful cast of over twenty hens, roosters, and peacocks. Scott’s birds are distinct and articulate characters, with names and family histories, agendas to pursue, and axes to grind. Their relationships are complex and multifaceted, and this cycle of paintings documents their adventures as they scheme, philosophize, maneuver for social position, and pursue higher truths.

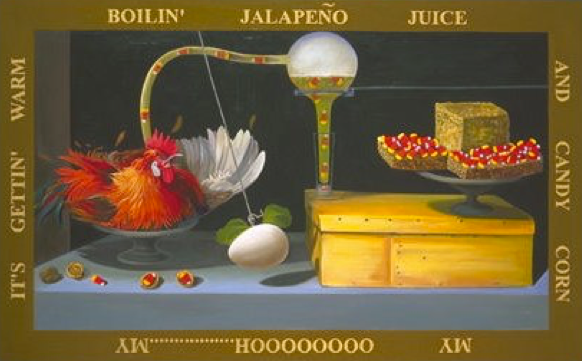

Foremost among the cast is one Miss Penny Peacock, who, Scott points out, is “not a girl at all, but a transvestite pullet.“ Penny is haunted by twin obsessions: gaining access to the metaphysics of (pro)creation, and a compulsion to avenge her ancestors who were sacrificed to the cause of the classical still life genre. Scott relates that Miss Penny’s mother took her to the Metropolitan Museum when she was five years of age to see a show of seventeenth century Dutch still life: “When she walked in the rooms it blew her mind because there she saw all of her relatives, dead, draped over tables, hanging from walls. Freaked her right out. From that day forth she vowed to rearrange any still life that she came into contact with.“ Penny’s mission is opposed by a mysterious group known as the TRA (Twisted Ridiculous Art, as well as “art“ spelled backwards). Scott notes that “They are not labeled as such, but it is probably suspect that they are curatorial types.“

The aesthetic agendas of Penny and the TRA reveal some of the satirical and conceptual underpinnings of this body of work, but Scott hints repeatedly at the possibility of multiple layers of meaning. Might not Penny’s creative quandary and obsession with revising the art of the past be symbolic of the dilemma of the artist in the postmodern era? Is there a deeper significance to the fact that Penny and her associates are all flightless birds? It is Scott’s intention that each viewer indulge his or her own interpretation of the parable of Penny and her cohorts, as he indicates through his protagonist’s opposition to the reactionary conservatism of the TRA. It is through this conflict that Scott expresses his objection to the narrow manner in which “art is interpreted and fed to most people by museum curators and institutions. They will tell you how you have to see this or that piece and will not allow for any leeway in your interpretation of it. This work attempts to unravel that concept a bit... I’m trying to suggest an approach that allows people to go into galleries and museums to discover their own creativity in interpreting art.“

It may seem that Scott has set himself an ambitious and difficult task. Could he not have decided upon a more conventional expression for his ideas? Undoubtedly so: Scott is a versatile and technically superlative painter, but he is also an artist possessed of a wildly fanciful imagination and an enigmatic sense of humor. Could he not have availed himself of a cast of characters more physically suited to the expression of human attributes? Yes again, but why go with the obvious? The simple fact is that the birds that appear in Scott’s paintings can all be found strutting around the artist’s own back yard in New Richmond, Ohio - willing and available models for his paintings. Scott is also amused by the profusion of bird and chicken-related phrases and metaphors in the English language, and sly word play figures prominently in the text that appears on his paintings and in the narrative he has written to accompany the work.

Above all else, Michael Scott wants his work to be accessible and to be enjoyed. He likes to think of his paintings as constituting a children’s fable for adults, offering us yet another reconfiguration of a traditional form - one intended to amuse as well as to instruct. Scott remarks, “My work was so serious for so long, and I began to find it rather oppressive. It’s nice to be serious and to show your sense of humor at the same time.“ So when next you find yourself in a museum or a gallery, standing in front of a still life painting, think of Miss Penny and her quest, and remember: a duck could be somebody’s mother.