THE Magazine July 2010

Buying beauty and selling beauty—what an idea!

—from the exhibition catalogue

In the late 1630s, the Dutch were going crazy

for tulips. Out of this mania came two most unexpected side

effects: the evolution of a mercantile-based middle class who

bought and sold flower futures, and an art just for them.

In their post-Reformation culture—minus a Catholic Church

to play the popish role of arts patron extraordinaire—paintings

in Northern Europe began to be made for, and bought by, the

well-to-do layperson eager to keep up with the Van der Joneses.

In fact, many seventeenth century paintings from the

Netherlands presented as subject matter—besides dazzling

still lifes of flowers as allegorical narratives—wholly middleclass

values such as spotless housekeeping, frugality, and

morality tales about marriage and fidelity. Relatively minor

collectors throughout history owe the allure of buying art for

their homes to the hard-working Dutch and their fascination

with the exotic Orient in the form of the Ottoman Empire’s

incredible tulip bulbs. The mysterious glamour of Turkey

and the allure of profit making combined to transform

seventeenth-century Dutch painting into the art that we

know and venerate today.

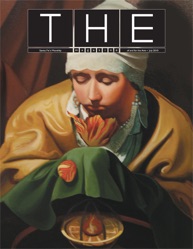

Michael Scott’s fascinating grasp of art history is

threaded through with the glitter of commercialism, and

conflated with the selling of the Wild West right here in the

Land of Enchantment, lies at the heart of this exhibition of

stunningly illusionistic oil paintings, starring the lovely tulip

in the role of Beauty, ever steadfast despite her apparent

fragility. Buffalo Bill Cody takes on the role of hero (perhaps

an alter-ego for the artist) in the saga told by some fifty

paintings; if he’s more than vaguely uncomfortable in the role,

we’re left uneasy by our own accountability as participants in

the defilement of absolute beauty as we try to make it ours.

Supporting roles include the American West as the whore

with the heart of gold, and the buffalo and Native American

as wise and valiant sidekicks. In this modern tableau, where

things are neither black nor white, culpability and innocence

battle for the confused hero’s heart and soul. Will he wind

up doing the right thing, or is the evil that emanates from the

black suits who manipulate bulb, land, and art prices behind

the scenes too great? The courageous sidekicks nearly die

in their efforts to save the hero, and all kinds of shenanigans

ensue, threatening Beauty’s purity even while she flies free,

above it all. Knowing what we know now, the question

remains: Why in heck don’t the sidekicks throw in the towel

and get the hell out of Dodge? It’s got to be that danged

West, with her golden heart and down-to-earth good looks.

Compared to Beauty, West’s is the kind of attraction that

lasts, magnificent to its last gasp. But that’s all fodder for the

sequel. This episodic exhibition leaves us with the certainty

that our characters are, if not doomed, in untold danger. This

is a tragic play presented in glorious carnival colors against the

sublime Western landscape, a stylized Moulin Rouge with the

moral “Never fall in love.” And its footnote: “Beauty, like love,

fades; only pictures last.”

Ranging in size from medium to extra large, Scott’s

canvases cover the theoretical territory of Manifest Destiny

as promoted in the nineteenth-century United States

through the landscape and the commercialism of secular art

as spectacle—a phenomenon as relevant today as it was in

seventeenth-century Holland. Scott’s subjects are narrated via

decidedly effective Baroque techniques including compressed

theatrical space and diagonal composition, a gem-like, returnto-

Renaissance color palette, enough trompe l’oeil to give

things a funhouse appeal, and exquisite still lifes situated

within a setting so energetic that the act of looking threatens

to exhaust the viewer. The paintings are placed in hand-built

frames that suggest the circus wagons and snake-oil sellers of

America nearly two centuries ago. There is real meat here,

and it’s not on the hoof. With this ambitious exhibition, the

artist takes on painting itself, its history, and our complicity

as consumers. Scott’s paintings tell a story of beauty and its

consumption—and our helplessness in the face of it.

—Kathryn M Davis

THEATRICALITY

My paintings are stage sets for conversation. I have one conversation with the work—the viewer has another

conversation with the work. Even though my paintings are conceptually driven, I don’t try to dictate how they

are to be seen. One of my favorite scenes from my boyhood is when Toto pulls the curtain back in The Wizard

of Oz and sees the wizard pulling all of the knobs in there, and Dorothy recognizes that the whole thing was an

illusion. I never forgot that. Painting is an illusion and I deal with that illusion as a conversation.

TIME

I try to make well-crafted paintings that convey a thought-out idea. There are a lot of nuances that occur within

that, and a lot of layers of information that happen. If I am clumsy in the process and don’t pull it off, then I fail

in what I’m trying to communicate. Because I create these bodies of work over a period of three to four years,

time is a factor. The trick is to have a concept that I can live with and develop over that period of time. Painting,

making art, is all about putting in the time.

WORDS

Our culture is layered and there’s a lot of information that comes at us. I find it very interesting to marry

typography and images, and particularly in this series where the work is like a poster or billboard, where

actual typography is incorporated to sell an idea, or an object, or a stage show.

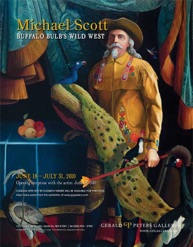

A TULIP OR SNAKE OIL?

Buffalo Bill’s Buffalo Bulbs Wild West Show has to do with the illusion of beauty. It is like any circus—there are tents

and little booths, and each painting works as a sideshow; you go through the curtain to discover the show inside.

In this series, Buffalo Bill is selling beauty to America. He brings the tulip—the most austere, aloof, and perfect

flower—from Europe to America. If the tulip (beauty) can be sold, what could be the downside of that? If it’s a

lie, then the tulip (beauty) is snake oil. Of course, Buffalo Bill was marketing to a gullible audience—which is not

so different than any other market-driven idea about economics. This body of work can be seen as a metaphor

for the current art world, where prices are astronomical for questionable work.

ROLE OF THE GALLERY OR DEALER

In an ideal world, the dealer handles an artist’s career in all of its aspects. This means the artist’s livelihood, his

sales, and the collections where the work is placed. (In many respects that’s what I’m painting about in my

work—that kind of art-world illusion is the veil that Toto pulls back.) A lot depends on where you are in your

career. You can’t put a blanket on everything and say it’s always the same with all artists. It changes from artist

to artist and dealer to dealer, and it changes based on your hierarchy in the gallery and in the art world. And you

have to be comfortable with where you are in that hierarchy. And you have to be okay with the fact that you may

not sell that series, or you may not sell that piece, or you may not be on top this year—just because you were on

top ten years ago. There are a bunch of different varieties of vegetables in the art basket, and there’s no rhyme

or reason to it, but that’s what makes it interesting. The main thing is to just continue to do the work.

RULES OF THE ART GAME

Don’t follow trends—that’s number one. Number two, learn how to survive and still create work. Number

three would be to position your work with the right gallery for consistent representation and exposure. And

number four, know that people who buy your work do so mainly because they’re interested in who you are as

an artist—they buy because they want a piece of you. And you have to be willing to give that piece of yourself in

a gentlemanly fashion, while having your own limitations about how much of yourself you give. I believe that as

long as you have clear boundaries you’re fine.

AUTHENTICITY

Authenticity has to do with an inherent energy that’s contained within a work. If you’re putting energy into

a piece—if it’s authentic and true to its core—then it’s there. That doesn’t necessarily mean it’s going to be

experienced by everyone, but I guarantee that once authenticity and presence are in there, they’re always

in there.

THE REWARD

If I have a good day in the studio, it doesn’t get better than that. As far as my career goes, I put faith in the

process, and the work guides my career and achievements. I know that I will never know how good I am unless

I push myself. Bottom line—it’s all about dancing with life, and for me painting is the vehicle. That’s it! D

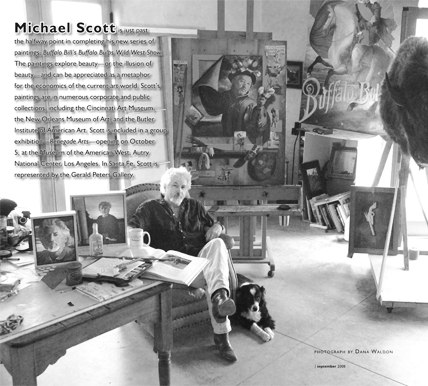

Michael Scott is just past

the halfway point in completing his new series of

paintings, Buffalo Bill’s Buffalo Bulbs Wild West Show.

The paintings explore beauty—or the illusion of

beauty—and can be appreciated as a metaphor

for the economics of the current art world. Scott’s

paintings are in numerous corporate and public

collections, including the Cincinnati Art Museum,

the New Orleans Museum of Art, and the Butler

Institute of American Art. Scott is included in a group

exhibition—Renegade Arts—opening on October

5, at the Museum of the American West, Autry

National Center, Los Angeles. In Santa Fe, Scott is

represented by the Gerald Peters Gallery.