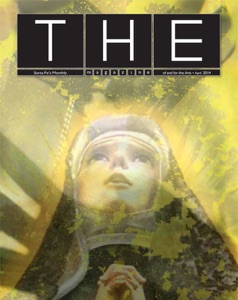

THE Magazine April 2014

IN THE PAST, MICHAEL SCOTT CREATED

SEVERAL CYCLES OF SLYLY

humorous narrative paintings, all rendered with virtuosic

technique in the style of Old Master portraiture, still life,

and tableau paintings. There has often been an element of

theatrical unveiling in his work, including painted curtains

that have been drawn apart. This present show, Found,

demonstrates a departure from using a didactic narrative,

and, in the artist’s words, is intended “to pitch you out in time

and space.” There may still be an unveiling taking place, but

the viewer takes on some responsibility and willingness to

bear with uncertainty; to slip back and forth across a delicate

threshold between the arbitrariness and the strictness

of collaged images; images that suggest a dialogue about

something that is not necessarily graspable in a literal way.

The means for suggesting this journey, according to Scott, has

been to present “porthole” ideas: layered forms and shapes

(haloes, chains, wheels, crosses, eggs, eyes) that in one way or

another spur the intelligence, seed the intuition, and

Last winter, while Scott was walking the streets of

San Miguel de Allende and Mexico City, he noted churches

whose exterior walls were beautified by exquisitely decaying

surfaces. Curious about the fact that the evolution of decay

could speak such poetry and evoke vibrant, non-specified

memories in a way that sterile, brand-new surfaces do not,

Scott entered the churches and observed the communicants

within. Repeatedly, he found people absorbed in prayer for

long stretches of time, apparently in intense communion with

images of the Virgin Mary, Mother of Christ. Scott wondered

what it was that the supplicants were doing and began to

question how the conversation with a higher power actually

transpired. He wondered what the underpinnings of religious

preoccupation actually are, but most especially, he asked,

“Who is Mary after all?” This wondering tied in with Scott’s

long-standing observation of a thriving mysticism and surrealism

present in Latin American cultures in general. What is it

that predisposes a people to line up on the street, paying

for street corner mystics to dispense purifying rituals,

replete with rings of fire and incantations? Gullibility

and susceptibility, the ardent belief in form—are these human

propensities a curse or a blessing? Scott recognizes that the

yearning for communion and surrender that is implicit in

formal acts of supplication is not to be despised. Efficacy

of means, whatever it takes, is primary. It is challenging and

daring to propose the idea of “The Holy Mother Mary”

as the driving concept behind a body of work. After all, just how

far can most of us go with Mary, an idea already so overloaded

with stale, limited concept? At first glance, not very far

at all. But once you take in the delicious pigments, the

arabesques of rhythm, the fine and subtle relationships

of texture in these fiercely worked collaged paintings,

and once you recognize the fusion of the decorative and

representative functions of the paintings that Scott has

made thoughtful efforts to tease out, the curious viewer

has an opportunity to take it further. Of course that’s true

with any painting: it lives only through the person who is

looking at it, attempting a dialogue and being willing to

follow unknown leads. This is particularly true with this

body of work, whose subject matter remains mysterious

and undecided.

The ideas that surface for me in these complex

paintings have small purchase in my own psyche.

I think: Mary as Mother, as Virgin, as Lover (Mary

Magdalene), and though this sounds like it could be an

apt, if extremely streamlined, portrait of the feminine

principle, I don’t know where to go with it. However

gorgeously conceived, these celestially kaleidoscopic

dreamscapes are unavailable to me as vehicles that might

inspire surrender. Though the instinct to establish some

kind of vivid, abiding contact with our basic nature is

fundamental to human life, our paths in this matter come

to us randomly, and only sometimes through religion.

Traditionally, God usually has rather definite intentions to

do something—say, to produce a world for instance—and

he may therefore be unnecessarily dramatic. On the other

hand, the manifestations of what are loosely labeled as the

feminine aspect tend to be more accidental and playful,

or embryonic: it embellishes itself, puts on make-up; it

expresses itself by demonstrating some sort of glamour,

whatever it may be: passion, aggression, seduction, loving

kindness, the sheer ferocity of life... attributes churning

beneath the surface of things. Maybe that’s what people

will find so compelling about Mary in these paintings:

her all-accommodating nature invites scrutiny, and if one

happens to have the right temperament, she may awaken

those mysterious capacities that direct us toward the

eternally flawless.

Most remarkable is the luminosity that these hybrid

works of art manifest. These intensely worked images

on stainless steel are the fruition of intense labor and

unique methodology—collaging, painting, grinding,

carving, varnishing—that allow a radiance to ripple

through, ever changing, according to one’s state of

mind. Their large format indicates that they are meant

to be looked up to—ideally, surrendered to—and gazed

at from different angles and distances. The full “pop”

will not occur in a cursory glance; rather, fresh images

and connections blossom over time and with patient

communion.

—Richen Lhamo