Farny’s Fables Reveiw

Michael Scott: Farny Fables

By Rinchen Lhamo

According to The American Heritage Dictionary, a fable is “ a usually short narrative making an edifying or cautionary point and often employing as characters animals that speak and act like humans.” Fable is alternately defined as a falsehood or a lie. The two meanings do not necessarily exclude each other, and when you think about it, any kind of story with an overtly instructive intent behind it (yawn) is bound to be soaked in provisional half-truths at best.

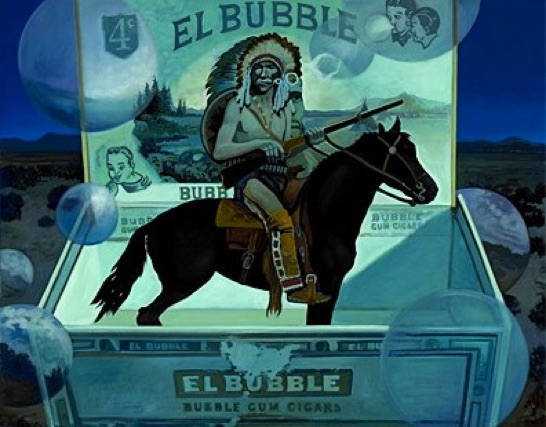

Michael Scott’s thirty-one large and magnificently garish oil paintings, collectively called Farny Fables, are meticulously and lovingly detailed works in which two meanings of fable perfectly dovetail in a highly theatrical, seamless narrative that was inspired, in part, by the life of Henry Farny. Farny (1847-1916) was a successful painter in his own time when there was an eager audience for sentimental depictions of American Indians and Western landscapes. Scott seems to be asking, “What if Farny had painted according to his own core sense of values rather than according to market values? What if he’d been more process oriented rather than product oriented? And so forth.

Scott has included roosters and chickens who, like the members of a Greek chorus, anticipate calamity and mirror it back to one another in dazed confusion. We know this because a printed narrative written by Scott accompanies the exhibition and, for the patient reader, successfully elucidates the themes that the painter has apparently been mulling over. Is luck the fruition of mining one’s own vision, or is it merely some mundane mechanical impulse that blesses the recipient when he is savvy enough (craven enough!) to gauge market trends and paint accordingly? And which kind of luck is the kind worth having: commercial success and money, or friendship and joy in the process of creating? Any half-sane person would want it all, but as the smartest people have always known, intention is all. In this case, the voice of proper intention comes through a grandmother (the first-person narrator of the text), who likes to bake cakes and is pretty good at it. It is she who channels the spirit of Vincent van Gogh, the very embodiment of incorruptible goodness and genius in this tale.

Scott has also transplanted Rembrandt’s good burghers of seventeenth-century middle-class respectability and prosperity into another version of themselves; set in the West, in a kind of indefinable time warp that could be now or then or never, they vaguely resemble a cadre of Dutch cowboys whose facility for working the market might as well be bred in the bone, given their inherited adaptability for all ventures of a mercantile nature. They’re not bad guys. You’ve got to love them cashing in on a good thing, in this case, twentieth-century Pop culture, replete with Vegas spectacle and culinary visions culminating in TV spots and “workshops on agave tasting…and bake [sic] dance class.” Scott’s whirly narrative goes dizzy with these spiraling embroideries.

As for the visuals, you might be tempted to see them as cartoons executed in lurid Technicolor masquerading as oil paintings. I suspect that that is part of the artist’s intention, and there’s no arguing his technical and fluid mastery. If Scott were in a circus, he would be the acrobat. You only had to walk into the large main gallery and let yourself be lifted up by the effusion of sumptuous and vibrant color. Beyond that, everything else was extra-pleasure, without pretense to absolute value.