Dairies of Little Red Hen Reveiw

Artist uses fowl in the fairest way

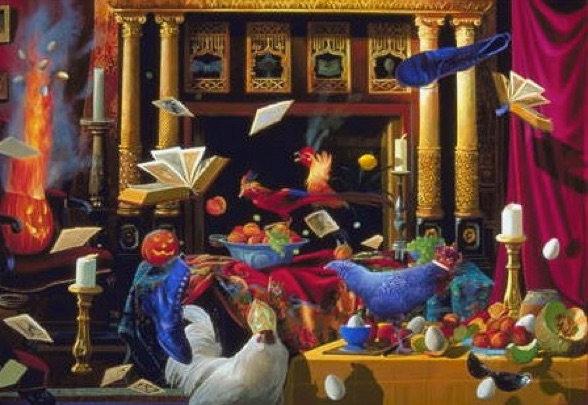

Painter Michael Scott beautifully renders

animals to tell a story about the human condition

By Marilyn Bauer The Cincinnati Enquirer

If you like Elvis, Marilyn, trompe l’oeil painting, chickens, feminine discourse or the American Southwest, you’ll want to stop by.

If you are interested in the grand conflict of man vs. himself, Jungian psychiatry, seances, sexuality, religion or exotic fowl, you will definitely want to stop by.

And if masterful painting by a nearly 30-year veteran of the Cincinnati art scene gives you a rush, you won’t want to miss The Diaries of Little Red Hen by Michael Scott. It opens Friday at the Weston Gallery.

But the Hen is more than a superior collection of paintings by a master of technique. It is also a book that follows the fascinating tale of a quest for the font of inspiration, with a cast of the most amusing fair weather fowl this side of Orwell. He calls the limited-edition book, which takes the form of a glossy-print, multi-ring binder, a "children’s book for adults." (It can be purchased at the exhibit for $25.)

"I call him an alchemist," says David T. Johnson, deputy director and chief curator at the Taft Museum of Art, of Mr. Scott. "He is a storyteller and a painter at the same time. The content is a work of art, as is his visualization. He has fused literary and visual traditions to create the story of the little red hen."

In the fable, little Miss Hen is taken under the wing of Penny the peacock, a cross-dressing pullet introduced in Mr. Scott’s first book and related paintings Penny’s Grand Vision: A Creation Story presented in 1979.

This time, Red is visiting Penny’s country home, an asylum for Con-cock-tion-ist theorists, to investigate the origins of inspiration. Things haven’t been going so well for Red. She’s having hot flashes. Her life is empty. She hasn’t met the right guy.

"I want to be appreciated for my mind," she clucks to Penny, "Not just my body."

Penny gives her protege a feather and a diary inscribed: "Look inside the feather’s eye to find your truth and not a lie." The gift sets the plot in motion and the hen on an Odyssian journey to find her bliss.

"The first story was more whimsical - although there are serious components - focused on the craziness in the art world," Mr. Scott says. "This one is more pragmatic. Penny gives the hen four inspirational cards, four concrete ideas, that are templates to direct her to places of inspiration."

Beyond the paintings

The paintings of the four cards - vision, perfection, divinity, frequency - are mounted just inside the entrance to the gallery, acting as mysterious talismans of what is to come.

"It seems as though he needed the addition of a book and a narrative to go beyond the paintings, to get the information out," says Dennis Harrington, Weston Gallery director. "It adds another dimension to the work. I think the paintings are incredibly beautiful and exquisitely detailed. It will be interesting to see how people respond."

Respond they will. Mr. Scott’s paintings are utterly unique. Large canvases vibrating with hallucinogenic color and Herculean attention to detail, they recall the work of 19th century trompe l’oeil artists such as William Michael Harnett (1848-1892) and John Frederick Peto (1854-1907). Doubly intriguing when considering a subtext of the narrative has to do with perception.

"I went to Paris and Brussels on a fellowship and also became attracted to the Harnetts at the Metropolitan," Mr. Scott says. "I was amazed. Things started to creep into my work pretty quickly when I got back: the space started flattening out; I dealt with issues of shallow space. A lot of it is the pun of art, the illusion of art. These really are stage sets the characters act out their scenes in."

These birds have character

The characters come from his farm in New Richmond where he has an aviary and henhouse inhabited by a motley crew of pheasants, peacocks, chickens and roosters. /div>

"It all started when the Phoenix (restaurant) commissioned a large painting from me of a grand feast," Mr. Scott remembers. "I incorporated peacocks, rabbits and lobster ‹ all the things a fine restaurant might serve ‹ into the painting, not as objects of the dinner, but as participants. I started buying birds, and before I knew it I had an aviary and a henhouse and animals I considered pets.

"They became characters. You notice . . . there is a pecking order to the henhouse and there is a dominant bird. And you start to see people you have met who remind you of the character of the bird. That’s where your imagination comes in, and the characters start to unfold."

Observing life

The little hen’s tale begins in the guest room of Penny’s house. Red has retired to study the cards. Exhausted, she falls asleep and has a dream so powerful she awakens seized with the compulsion to write, er chicken-scratch, in her diary. In a frenzy (of dare I say inspiration?) she channels the genome code for Elvis, whom she believes is the perfectbird for her.

"Each room is a different conversation," says Mr. Scott of the story’s structure and Red’s journey through the house. "And in each room, the conversation expands."

To illustrate this particular conversation, Mr. Scott paints an elaborate Victorian room dominated by a pinup painting-within-a-painting of Marilyn Monroe. In the center of a maelstrom of flying peaches (Red sees herself as a succulent peach about to be seduced by the King), leopard pillows, crockery and drawings of cocks, the little hen in a diamond necklace stands entranced.

The painting is a magnificent tableaux rendered in the Flemish tradition, with the incorporation of gold leaf and infused with an opaque, jewel-like quality. But it is also a cockamamie, almost surreal depiction of the hen’s inner life.

“"I am painting my process,” says Mr. Scott. “The story was written after all the paintings were completed. That’s how it works. Your antennae are up and the ideas are moving. You’ve been given the inspiration card so you now have the symbol of the idea and the concept. ... Images come and you start making these little drawings. You have no idea whatsoever where it’s going until after maybe 12 paintings."

“The story that has evolved from this is incredibly complex and elaborate," Mr. Harrington says. ”I have often thought, "Where does this come from?“ But I think it comes from his study of art history and his own observations of daily life.“

”A female story”

One of the situations Mr. Scott has observed is the feminine quest for an unreachable ideal of beauty.

"Red Hen is a female story," he says. "It deals with the conflicts of being a woman in today’s culture, where you are given so many signals about what perfection is.

"Sally Shovel (ostrich curator) is another example. In her quest for pure form, she wants to suck the air out of art and keep it in a vacuum where it will be more pure. You find this in a lot of installations in contemporary museums. They don’t reach the viewer because they are so conceptually driven all the emotion is sucked out. The question becomes what is more beautiful, that which is man made or that which is made by God?"

The Sally Shovel painting shows the big bird inside a glass-encased vacuum contorted so that her head is under her feathery body, which is planted over a Faberge egg. The text reads: "She is questioning which is more perfect - a Faberge egg or her own orifice."

Art patrons abound

Art world habitues are mercilessly skewered throughout the narrative. The Admiral, a rooster equal parts pope and Buddha, has a painting he lovingly rendered rejected by the Ohio State Fair. "It didn’t meet a curator’s vision of what art should look like," the text explains.

The Free Ranger, a chicken who channels Vincent Van Gogh through ears of corn, agrees to "make paintings for the wine-tasting crowd" but only if he can do it in a museum as performance art.

“It’s a tough crowd," says Mr. Scott. "Part of what I do with these works is to point out the emperor sometimes has only a few clothes on.”

"Technically he is a fabulous painter," adds Mr. Johnson, noting Mr. Scott is able to incorporate the accomplished application of paint with commentary on today’s society. "Being a curator of "dead art,’ I like that in a contemporary painter. It’s what interests me."

The masterpiece of the show, "Voodoo-Cock Soothsayer," is pivotal in the visual and written narrative. Everything that has come before, much like the refrain of a song, is repeated: the four cards, the colorful characters, the peaches. Little Miss Hen crosses the time-space continuum into a new reality where everything, especially art, lives in both historical and eternal time. Elvis is finally made manifest in a whirl of sound and golden oldies: "It’s Now or Never,“ "Are You Lonesome Tonight” and "Love Me Tender.”

“The painting sums it up,“ Mr. Scott says. “In order for your life to inspire, you need to cross from historical time to eternal time. “Life is short, art is long.’ Seneca says it clearly. That’s how it works.

But as is often the case, when Hen gets her man, she decides he’s not what she needed after all.

“She’s learned what she thought would bring her real happiness, was only a sideline,“ Mr. Scott says. “Understanding herself is what brought her happiness. She got a job.“