Art & ANTIQUES

Dog Star

February 2012

by: Sarah E. Fensom

Each February, the American Kennel Club stages the Westminster Dog Show, a tradition that ranks as the second-longest-running sporting event in America (after the Kentucky Derby). The event, which premiered in New York City in 1877, actually predates the club itself, which was established in 1884. This year will mark the 136th go-round of the show, which describes itself as “a celebration of the wonderful canine spirit, reflecting our emotional and spiritual attachment to our dogs.” This description is just as apt for representations of dogs in art. Whether an ancient symbol associated with the afterlife, a companion in sport, a languid figure on a cushion or a tenacious poker player, the dog has been a muse to countless artists and a delight to countless viewers.

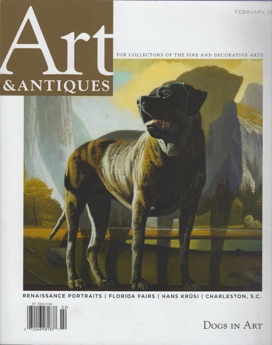

When the first kennel club was established in England in 1883, so were the standards of breed and the regulation of dog shows. As a result, dogs began to be represented in art in a new style, one that William Secord, founder and director of William Secord Gallery in New York and the foremost expert on “dog art” in America, refers to as the “purebred dog portrait.” “With the establishment of the kennel club,” Secord explains, “the way the dog looked became very important. There was a type of painting that developed because of this. What I call the ‘purebred dog portrait’—four on the floor, facing left, head towards the viewer—to show how the dog conforms to the standard of the breed.” These sorts of portraits are in many ways the equivalent of seeing a dog in show, sharing the same intention of capturing the essence of the breed as a whole and the grace and pedigree of the particular dog himself.

Secord, in his 1989 book Dog Painting: A History of the Dog in Art, the first and still definitive tome on the subject, defines the heyday of “dog art” as the period between 1840 and 1940, thriving particularly in England. Besides the establishment of the Kennel Club, Secord cites the rise of a moneyed British middle class and the canine-loving Queen Victoria as factors in the dog’s popularity with art collectors. The Queen, who had more than 75 dogs at a time in her kennels at Windsor, was frequently presented with exotic dogs from around the world—a Pekinese from China, a Great Pyrenees from Prince Leopold of Belgium, and so forth. She was in the habit of commissioning portraits of her dogs by top artists, which created a trend.

The golden era of the genre was a natural outgrowth of Britain’s well-founded tradition of portraiture, canine or otherwise, according to Alan Fausel, head of the fine arts department at Bonhams New York, which holds an annual sale of dog-related art to coincide with Westminster (on February 15 this year). “Britain got a late start in the history of art,” says Fausel.“Being Protestant, it didn’t have the same tradition of history painting, but it did have a strong tradition of portraiture. We see it in the 18th century with artists like [Thomas] Gainsborough and [Sir Thomas] Lawrence—it feeds right into painting your dog, and to someone like [George] Stubbs, who was famous for dog and horse painting.” Fausel adds that “it has to do a bit with the aristocracy there, venerating your ancestors and your family.”

Fausel says that the British painters go for higher prices, though there are a few Dutch and German artists worth their salt. Secord sees a difference between British dog art and that of other countries: “Belgian, Dutch, Flemish and German artists were more influenced by realism, depicting the dog the way it really looked, with dirt on it’s coat and slobber and that kind of thing. You see Alfred Stevens, who’s Belgian, do street dogs and dogs that are suffering, which in England you never see. British depictions were more idealized. They want it pretty.”

The “purebred dog portrait” was not the only fashionable type of dog painting during the 19th century. Representations of dogs in the field and at work, though contextually very different and even then, as they are now, for a different sort of collector, were at their height of popularity and quality. The title of Bonhams’ auction, “Dogs in Show & Field,” suggests that it caters to those looking for the “purebred dog portrait” and to enthusiasts of hunting scenes. Of these two categories Fausel notes, “The ‘purebred people’ are going to pay 5, 10, maybe 20 thousand dollars for a portrait, whereas for collectors of dogs of the hunt, foxhounds, gun dogs, retrievers, spaniels, setters, pointers—the prices go upwards of that, with the British painters going for higher prices than say, Dutch or German examples.”

Up for grabs at this year’s sale are two painting by British artist William Henry Hamilton Trood, who was lauded in Victorian England for his depictions of dogs and other animals. The first, Hounds in a Kennel (est. $60,000–80,000) depicts a group of dogs looking at a robin perched right outside their kennel door. In this riff on a hunting scene, the dogs show a keen interest in the bird and an unfailing instinct. The second, titled Dejeuner (est. $50,000–70,000) is a genre painting that captures a peaceful moment among a group of puppies, ducklings and, perhaps most surprisingly, a cat.

A contemporary of Trood, Edwin Henry Landseer, is considered by Secord as “the top” when it comes to dog painting. A favorite portrait artist of the Queen’s, Lanseer, who was rumored to be able to paint with both hands at one time, depicted the royal family and the royal dogs many times over. Perhaps most famous is his 1841–45 painting Windsor Castle in Modern Times, a representation of the domestic bounty of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert complete with terriers, a boxer and slain fowl—a true marriage of the “dog on a cushion”-type painting and an “after the hunt” image. So influential were Landseer’s dog paintings that a variety of the Newfoundland breed was named after him, in homage to a series he painted showing the dogs performing water rescue.

Breed was a major factor both in the choice of subject during the height of dog painting and in the salability of dog paintings on today’s market. The Cavalier King Charles Spaniel was perhaps the most regularly depicted dog in the 19th century, as were boxers and fox terriers in sporting images. The more popularly represented breeds were the ones that “for some reason had a pride of ownership, where those commissioning paintings wanted them to be depicted,” says Secord. “You rarely see herding breeds or working dogs depicted.” According to Fausel, “the bottom of the pack, surprisingly, is Lassie and Rin Tin Tin. In the 1920s they were huge, but you can’t get $800 for a German Shepherd today.” This discrepancy is due mainly to when these paintings were made. Fausel notes that today’s most popular dogs, golden retrievers and black labs, “were not popular until the 1910s. In the work of Reuben Ward Binks, we see a few labs, but he was painting until the 1940s.”

The ownership of certain breeds today influences collectors’ desire to own certain paintings. Many will only seek out depictions of breeds that are familiar to them or that bear a sentimental value. Breed becomes a non-issue with only the finest examples of dog art, which, as one would expect, favor the popular breeds oftheir time. Secord says, “I have clients who only collect contemporary art, but they want a Cavalier King Charles Spaniel in their library.”

So what about dogs in contemporary art? There is a market for contemporary dog portraiture, mostly among those who are both avid art collectors and dog lovers. Christine Merrill, an artist Secord represents, has been specializing in dog painting since 1975, in a style that is an ode to classic “purebred dog portraiture.” New York artist Mimi Vang Olsen is a West Village mainstay whose folk-art inspired depictions of dogs (and cats) are as colorful as they are endearing.

There are, of course, contemporary artists who don’t make “dog art” per se, but have become famous for using images of dogs in their work. William Wegman, who gained popularity for photographs and short videos of his Weimaraners, immediately springs to mind. Dressing the sleek and steely-looking dogs in overalls, placing them atop stools or posing them with banjos, Wegman’s photographs personified the Weimaraners as sullen or at times suspicious-looking characters, or employed their lean bodies as sculptural elements.

George Rodrigue’s blue dog is another famous canine in art. This ubiquitous image has its own lore, dating back to 1980, when Rodrigue was commissioned to interpret Louisiana ghost stories visually. When developing the image for the loup-garou, a werewolf-type creature that lurked around cemeteries and sugar-cane fields, he was inspired by the countless photographs he had taken of a terrier-spaniel mix named Tiffany who accompanied the artist in his studio. However, Wendy Rodrigue, the artist’s wife and publicist, insists that “the series was never really about Tiffany—or even, honestly about dogs. He looks at his work more as shape, color and design, so he’s not particularly pulled towards ‘dog art.’”

In Rodrigue’s original representation of the loup-garou, a greyer, more ghastly dog sits in front of a haunted red house on what looks like flattened tombstone. Rodrigue, an accomplished portrait artist with a penchant for bayou scenes, began to reproduce the loup-garou in other paintings, but it wasn’t until a show in Los Angeles in 1988 that he was approached by gallery-goers with questions about the “blue dog.” He eventually changed the creature’s red eyes to yellow, and the blue dog began to gain popularity, eventually showing up as a popular image in American culture, in Absolut vodka and Xerox ads and galleries around the country.

Turning the idea of dog art and the purebred dog painting on its head is Michael Scott’s show “The Doggie Dairies” at Gerald Peters Gallery in New York this month (through February 17). Using rescue dogs as his muses, Scott has recreated Old Master paintings and classic modern scenes with canines near candelabras and floral arrangements, wearing fancy hats and nuzzling bowls of fruit. Scott has used his bold palette to create cheeky Western scenes, fluffy nebulous skyscapes, and trompe l’oeil cabinets of curiosities, but he is new to painting dogs. The opulence of his scenery coupled with the relaxed, everyday quality of the animals serves as a reminder that whether on cushions or toting fowl, depictions of dogs are perhaps at their best when they make the viewer want to reach through the canvas and scratch an ear or two.